This article is for general guidance only and is not financial or professional advice. Any links are for your own information, and do not constitute any form of recommendation by Saga. You should not solely rely on this information to make any decisions, and consider seeking independent professional advice. All figures and information in this article are correct at the time of publishing, but laws, entitlements, tax treatments and allowances may change in the future.

For many of us, the state pension is more than just a payment; it’s a promise. It represents a lifetime of work and national insurance contributions, providing a reliable source of income that forms the bedrock of our retirement plans.

But as we all live longer, the cost of providing that well-earned support is rising, forcing a national conversation about the future. News that next year’s state pension increase will be 4.8%, well above inflation, has fuelled the debate. Below, we set out how the system may need to adapt in the years to come.

What’s on this page?

The state pension is the second largest expense for the government, after healthcare, and the bill has risen steadily.

Figures from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) show that while annual spending was around 2% of GDP in the mid-20th century, it has increased to around 5% of GDP, around £140bn.

And this figure is only set to get bigger. OBR projections suggest that, by the 2070s, the bill for the state pension will be 7.7% of GDP.

The increased spending in recent decades, and the projected increases, are largely down to increased life expectancy, on top of the annual rises built into the triple lock, which was introduced in 2011. And falling birth rates mean that paying the pensions bill is an even greater challenge.

Helen Morrissey, head of retirement analysis at Hargreaves Lansdown, says: “It’s causing huge challenges for the state pension. An increasing number of older people being supported by a smaller working population means the cost of providing the state pension has increased. Steps need to be taken to ensure it remains sustainable long term.”

The debate has been fuelled by the fact that average earnings growth in May to July (one of the components of the triple lock) means that the state pension is set to increase well above inflation in April 2026, almost certainly by 4.8%. From April 2026 the full new state pension is expected to be £241.30 a week or £12,547.60 per year. The basic “old” state pension will be £184.90 per week or £9,614.80 a year.

Reforming the state pension is politically fraught. Although a recent survey by Hargreaves Lansdown found that 46% of working age adults didn’t expect it to be there when they retired, we’re incredibly protective of it.

Politicians of all colours know making significant changes puts their careers on the line. The triple lock is a prime example of this, with the current government committed to a manifesto pledge to keep it for this parliament, and the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats having committed to keeping it. Reform UK has not yet announced its policy on the triple lock.

Pensions expert Tom McPhail adds: “I spoke to a senior politician recently and they said you just can’t touch the triple lock. It’s too toxic.”

Despite this, some politicians are concerned that the policy is unpopular with younger voters. Conservative MP Tom Tugendhat recently said that voters were seeing “an economic system which has effectively become a Ponzi scheme for the old...the entire economy is now geared towards a bunch of people who are ageing”. He told the party’s annual conference that the triple lock is “simply not sustainable”.

As well as risking voter revolt, any changes to the state pension are part of a much broader balancing act. Changing the pension age, the amount that’s paid or who receives it can have a knock-on effect on other areas including welfare support, how much people save towards their retirement and even the state of the economy.

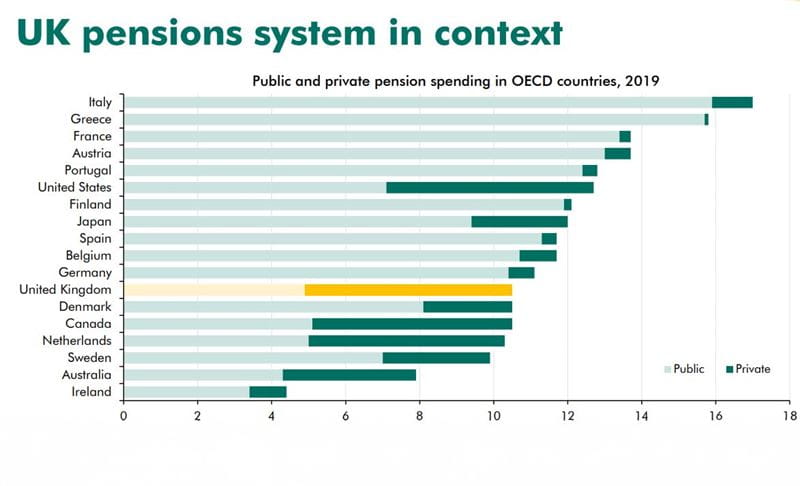

While the triple lock is often portrayed as generous, the UK spends less than many European countries on pensions. According to European Union figures, spending on pensions was equivalent to 12.2% of the EU’s GDP in 2022.

The highest-spending country relative to GDP was Italy at 15.5% of GDP, followed by France (14.7%), Greece (14.3%) and Austria (14.2%). The lowest spending relative to GDP was in Ireland (3.8% of GDP) and Malta (5.6%).

The most generous state pensions are in Iceland, Luxembourg, Norway, Denmark and Switzerland. In Iceland, the average pension spending per pensioner is €35,959, or around £30,251 – around two and a half times the UK levels.

Compared with the other 37 OECD countries, the UK is near the lower end of the scale in terms of the proportion of pensioner income that comes from state funding (the state pension and benefits like pension credit). Instead, the UK relies relatively more heavily on workplace pensions.

The UK ranks 14 out of the 34 OECD countries where data is available, for the number of people over 65 living in relative poverty (that is, compared with the rest of the population of that country). It has more pensioners living in relative poverty than most Western European countries. Countries with larger numbers of pensioners living in relative poverty include Estonia, Korea, Latvia, the US, Australia and Ireland.

It may be difficult but, as the costs keep rising, politicians need to explore the options available to them to make the state pension more affordable and sustainable. Here are some of the changes they could consider:

Improvements in life expectancy mean we’ve already seen the state pension age increase, with age 68 pencilled in for between 2044 and 2046. But, as the government is required to regularly review state pension age, these dates and ages could shift. Morrissey says: “The review is looking at whether the current timetable should remain in place or we need to accelerate the shift to age 68. We may also see timetables put in place for a state pension age that increases to 69, 70 or even beyond.”

McPhail is keen to see it pushed even further, advocating a state pension age of 75 by 2072. To offset the longer wait, he proposes a higher level of state pension. “Giving people a state pension they could live on at age 75 gives them something to aim for,” he explains. “Not everyone can work until that age so they could draw a lower amount earlier or plan ahead by building up enough private pension to cover the gap.”

Not everyone is a fan of such a big jump in state pension age. Heidi Karjalainen, senior research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, says it would affect some groups more than others. “It would have a bigger hit on lower earners as they tend to have a lower life expectancy,” she explains. “Our research has also shown that women out of employment in their late 50s tend to be harder-hit by state pension age increases. There needs to be targeted support alongside any future increases.”

Steve Webb, partner at LCP and former pensions minister, is also sceptical about the need for such a big jump. “State pension age will continue to rise but I don’t expect it to increase to 75,” he says. “If government needs to increase the number of people economically active, there are three other levers it could consider – fertility; economic migration; and supporting people who are economically inactive, such as the long-term sick, into work.”

Means-testing would target those who need the financial support, much like other benefits such as pension credit and council tax support, but this shift to fairness can feel anything but fair.

To illustrate this, Webb points to the challenges around introducing means-testing. “The government can’t introduce means-testing for existing pensioners, as they expected to receive the state pension,” he explains. “And, if it sets a future date, it could face claims of discrimination.”

There is also a risk that it would discourage people from making their own pension provision. By setting an income level at which someone would lose their entitlement, it could mean more people opt out of private pensions.

Introducing means-testing might not be the most practical option for the UK right now. It already exists in Australia, where eligibility for the state pension is based on income and assets.

The Australian private pension market is more developed than the UK’s, with employers paying a minimum 12% of employees’ income into their pension, significantly more than the 3% minimum that UK employers currently contribute.

Although he’s not a fan of means-testing, McPhail sees increased pension savings as a key part of any future landscape. “We need to get to a position in the UK where everyone is saving a decent amount for retirement. Employer contributions need to rise to around 10% and, while it’s difficult to push additional costs on to businesses, we could do this over the next 10 to 20 years.”

The triple lock was introduced in 2011 to ensure the state pension kept pace with inflation and enable pensioners to maintain their standard of living. Before that, the state pension had been falling relative to average earnings since 1980, when the policy of increasing it in line with earnings was ended.

The triple lock increases the payment every year by the highest of 2.5%, inflation or average wages. Morrissey says: “It’s led to some big increases in recent years so there is potential to reform it.”

While these big increases are great news for pensioners, the triple lock isn’t so good for the government as it creates a lot of uncertainty around future costs. As an example, the OBR’s findings show the triple lock has already cost three times more than expected, at around £15bn by the end of this decade.

To inject more certainty, Karjalainen would like to see politicians take a view on where the state pension should be in relation to average earnings. “It could set a target level and keep the triple lock in place until we reach that and then increase in line with earnings,” she explains.

There’s plenty of support for ditching the triple lock. Webb, who introduced the triple lock as minister in the coalition government, previously said it should be kept until the state pension reached a “reasonable share” of average earnings. He now advocates a double or smoothed earnings lock.

Mike Ambery, retirement savings director at Standard Life, suggests tying any increases to the Retirement Living Standards produced by Pensions UK (formerly the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association). “There’s no need for all three,” adds Ambery. “Matching the minimum retirement living standard would help with projections and ensure that pensioners had enough to live on.”

A review of the triple lock may be off the table for a few years due to the government’s manifesto pledge, but some reforms to the state pension system are expected before then. Ongoing government reviews are looking at the state pension age and exploring retirement income adequacy.

But, although this might mean increases to workplace pension contributions or another step up in the state pension age, don’t expect changes to happen overnight. Ambery says: “The current system is unsustainable but any change will need to be introduced gradually and with plenty of consumer education. We might have new rules but major changes are unlikely until 2030 at the earliest.”

/mature-couple-looking-at-taxes.jpg?la=en&h=650&w=1400&hash=5CFABEEDC751F26D56DD3E85749E3C36)

Current rates, when you can claim, eligibility, and how to check & boost your entitlement.

Women’s pensions tend to be smaller than men’s. Find out if you can boost your pension.