Think of a king and your brain is likely to conjure up a portrait of Henry VIII. It’ll probably be one of the Hans Holbein ones where he’s all square: square ends to his feet that are planted wide apart so they’re directly underneath his square shoulder pads, framing his big square chest.

Plonked on top, his large square head, with beard covering the bottom two corners and hat covering the top two – the slightly jaunty angle of the latter utterly undermined by the extremely unjaunty look on the cruel, piggy-eyed face.

He’s such a famous king that almost anyone who would ever buy or read a history book in English knows the main things about him.

There are six of them and they’re his wives: divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived. Now, as then, they only seem to matter in terms of their unruly relationship with him.

We all know men like that – at least Henry had the excuse of being king.

The odd thing about Henry VIII is that we know such a lot about his feelings and desires. He lived his life in public, like a cross between Kerry Katona and Vladimir Putin.

We know of his physical vanity, his lusts, his desperation to have a son, the many crises in his love life, his conflicted spirituality, his young athletic sexiness, his embarrassing weight gain and increasing physical decrepitude.

The start of Henry’s reign was quite nice in a boring sort of way. Everyone thought he was very handsome and clever, and he did all the things that were expected of him.

He married Catherine of Aragon, his brother’s widow, in 1509, thereby cementing an alliance with Spain.

By the late 1520s, Catherine had got too old to have any more children. Of the several she’d had, only one had survived infancy and that one, horror of horrors, was a girl and Henry was convinced that he needed a male heir.

At the same time, Henry was becoming infatuated with the much younger (than either him or Catherine) Anne Boleyn.

Henry became convinced that the reason he hadn’t had a son was that he should never have married his brother’s widow, so God was cross. He told his chief minister, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, to persuade the Pope to get his marriage to Catherine annulled.

Now, Wolsey was an exceptionally capable man. Sadly, however, he couldn’t achieve the impossible and that’s what the Papal annulment of Henry and Catherine’s marriage turned out to be.

The Pope said no. Egged on by reformers such as Thomas Cromwell, his chief minister from the early 1530s onwards, as well as Thomas Cranmer, who became Archbishop of Canterbury in March 1533, Henry married Anne.

Cranmer annulled Henry’s marriage to Catherine, declared the king’s marriage to Anne to be valid and, on 1 June, crowned her queen.

In 1534, Henry declared himself the head of the English church.

This wasn’t quite the same as turning the country Protestant, but the many people in Henry’s circle who were in favour of the Reformation delightedly saw it as a step in that direction, even if Henry himself blew hot and cold over ditching tenets of the faith he’d been brought up in.

The only two tenets he was totally comfortable with ditching were 1) his having to obey a man in Italy who didn’t seem to understand how sexy Anne Boleyn was and 2) there being monasteries all over the place in possession of lots of land and wealth that Henry couldn’t nab even though he could think of thousands of fun ways of spending it.

Henry and Anne did not have a very happy marriage. She kept answering back, which, you will be amazed to hear, Henry didn’t like, and she gave birth to a daughter, which he liked even less. Also, she managed to fall out with Cromwell despite both of them being Protestants.

In January 1536, three years into marriage, Anne was pregnant again and had a strong sense it was extremely important that she give birth to a boy.

However, an attractive, quiet, amenable and deferential young woman by the name of Jane Seymour had started hanging round the court and laughing at the king’s jokes and this made Anne anxious.

Then, one day, Henry suffered a jousting accident in which he hurt his leg and, by one account, was unconscious for two hours.

The leg injury troubled him for the rest of his life as it developed into a revolting, purulent ulcer which stank and caused him agony.

The shock of the jousting accident is said to have been what caused Anne to miscarry a male child a few days later.

Henry was not very sympathetic and allowed charges of adultery to be trumped up against her. She was executed in May 1536 and Jane Seymour was betrothed to Henry the next day.

‘Jane Seymour was his ideal wife: she didn’t argue, she gave birth to a boy and then she promptly died without him having to kill her’

Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light, based on the final novel in Hilary Mantel’s trilogy, begins here – after Anne’s execution – with Henry (played by Damian Lewis) about to marry Jane.

She was his ideal wife: she didn’t argue, she gave birth to a boy and then she promptly died without him having to kill her. What a catch.

Henry claimed to be heartbroken at his wife’s passing, though there’s a certain amount of self-pity that has to be waded through before we can properly discern the sincerity of the emotion.

Cromwell [played by Mark Rylance in the BBC series] was riding high in 1539 when he organised the king’s next marriage to Anne of Cleves.

Her father was the Duke of Cleves and this was part of Cromwell’s plan to cement an alliance with the leading Protestant states of western Europe.

He dispatched the great painter Hans Holbein the Younger to do a portrait of Anne to show to Henry.

The king responded enthusiastically to the portrait, which is interesting because I wouldn’t say it looked exactly sexy. It wouldn’t make it into a Pirelli calendar. It’s quite a plain picture of a normal-looking woman.

Nevertheless, it clinched the deal for Henry and a marriage was organised. Poor Anne travelled to England, all nervous and excited, and then Henry took one look at her and decided he didn’t fancy her at all.

But he still married her a few days later, which seems to me to compound the awkwardness.

Henry couldn’t get it up and decided that was entirely Anne’s fault and not his for being a boozy old fatso with a rotting leg. By the standards of most relationships, Anne was quite badly treated.

By the standards of Henry’s wives, she’s probably second luckiest.

The marriage was swiftly annulled and for the rest of her life she lived in England in quiet retirement. Nevertheless, the whole episode was pretty embarrassing for Henry, so Cromwell’s days were numbered.

In April 1540, in the wake of the Cleves fiasco, Cromwell was made Earl of Essex – a meteoric elevation. But it seems Henry was just toying with him.

Two months later, he was arrested, attainted and, on 28 July, executed. Henry didn’t watch it happen because he was getting married that day.

Henry’s fifth queen was Catherine Howard, niece of the unruly Duke of Norfolk. The king soon regretted it.

He never had a minister as capable as Cromwell again and Catherine was as unfaithful as Anne Boleyn was accused of being. She was executed in 1542.

But the bloated, wheezing, rotting, increasingly enraged and immobile old romantic hadn’t given up on love. The following year he married another Catherine, this time Catherine Parr.

She was a reformer and seems to have been an intelligent, humane woman who managed to make the old wreck of a king feel attractive and loved.

She was also instrumental in reconciling him with all of his children.

His daughter by Anne Boleyn had been removed from the succession and declared a bastard by an act of Parliament just as her half-sister Princess Mary had been but, under a third Succession Act in 1543, all the king’s children by his many marriages were legitimised and returned to the line of succession. One great big, extremely f***ed-up family.

They would now have the same inheritance rights as if they’d all been born to the same queen.

Edward first, because he was a boy, then the girls, starting with Mary and followed by Elizabeth. And that is exactly what happened: they all reigned one after another and died childless.

The Tudor line, which Henry had wreaked so much havoc trying to secure, was doomed anyway.

Extracted from Unruly: A History of England’s Kings and Queens by David Mitchell (Penguin, £10.99), out now in paperback.

Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light comes to BBC One and BBC iPlayer this month.

The Bafta-winning actor had been so successful at losing weight, he had to fatten up with a strap-on false belly for his latest role.

The presenter on inspiring the next generation and how daughter Zoe is bouncing back after leaving Radio 2.

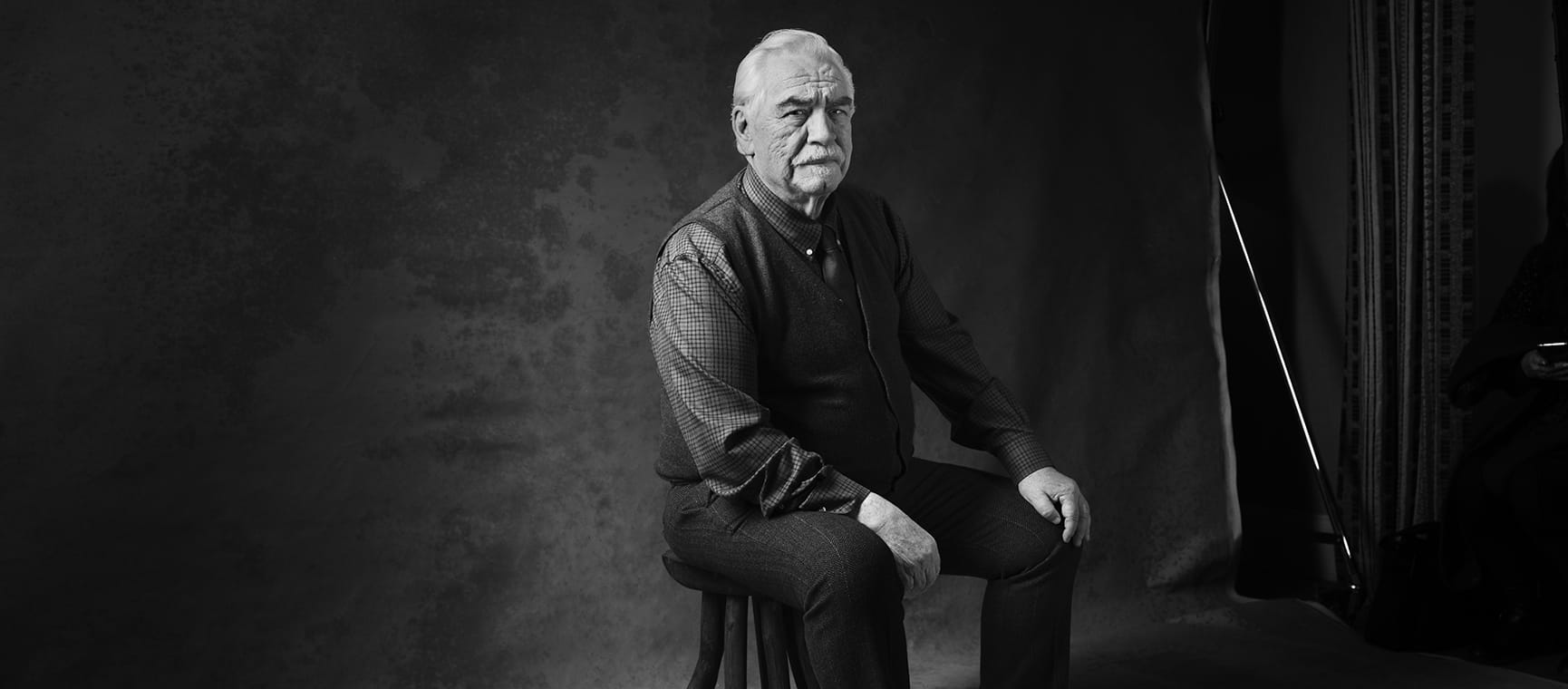

The Scottish actor on how he’s still asked to repeat Logan Roy’s most famous catchphrase.

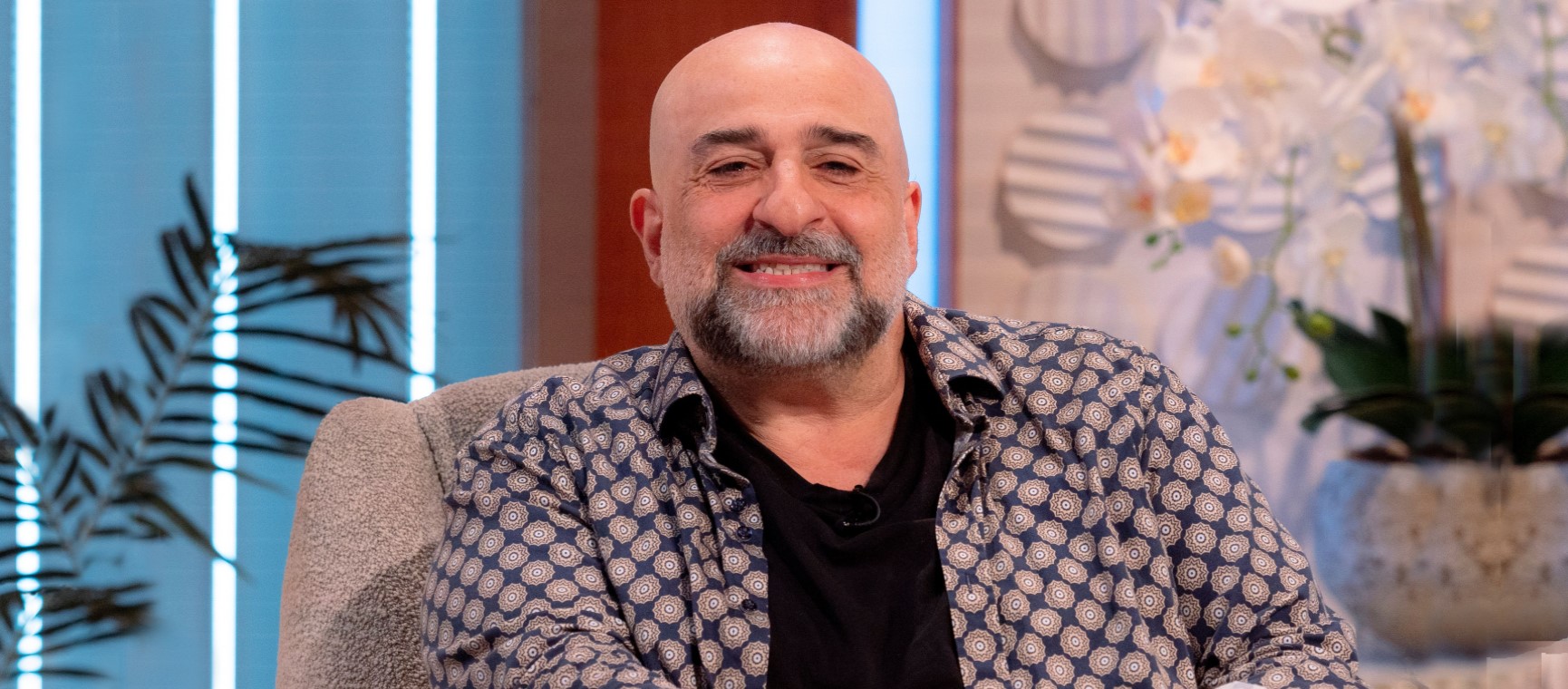

The presenter reveals his surprise contestant and how Richard Osman ‘bullied’ him into writing his debut novel.

The TV adaptation of Rivals has has been judged a rip-roaring success. We caught up with the book's author.

The BBC Radio 4 Today presenter reveals the responsibility and privilege that goes with her job.

The presenter on being sacked by the BBC and why her views are 'career suicide'.

The best-selling author says Pilates has changed her relationship with her body.

Stop smoking, go for a walk and do puzzles, says the veteran newsreader.