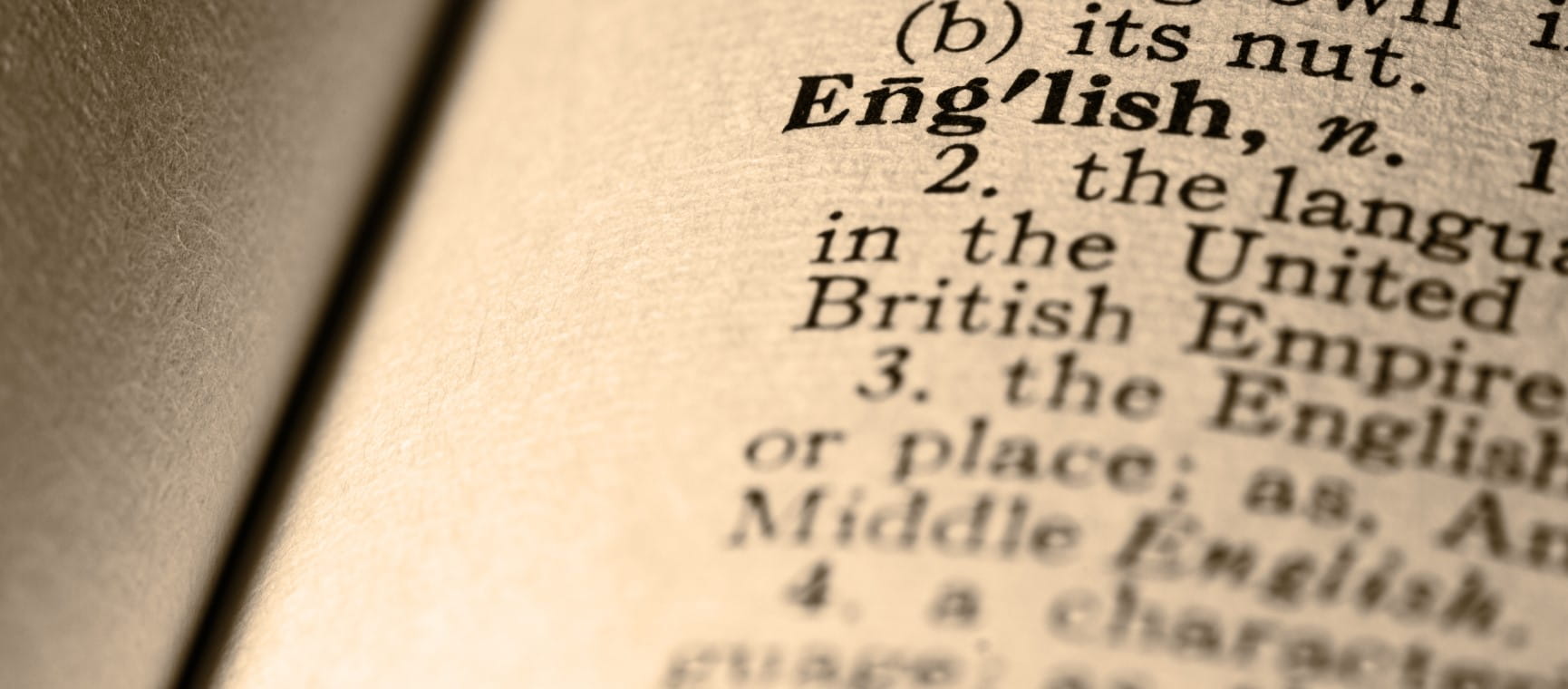

When the mother of all dictionaries, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) was first proposed in 1857, the founders wanted it to include every word in the English language.

Not only that, they also decided it would trace the history, and give the biography, of each word from its very first appearance in a written source to the current day, and provide examples of how it should be used in context.

The founders of the dictionary – a small group of men in Oxford and London – realised they could not do such a mammoth task alone, so they invited people around the world to help by sending in quotations from books they were reading, on small 4 x 6-inch ‘slips’ of paper, each focusing on a specific word.

When the mother of all dictionaries, the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) was first proposed in 1857, the founders wanted it to include every word in the English language

They had no idea whether anyone would respond to their appeals in newspapers, journals, clubs and societies. But it was a huge success.

So many people wrote in that Royal Mail had to put a red pillar box outside the house of James Murray, the longest-serving editor, to cope with the volume of his letters in reply.

If you go to Murray’s house at 78 Banbury Road, Oxford, it now has a blue plaque on it and the red pillar box is still there.

When they began the dictionary in 1858, the founders thought it would take two years to finish. It ended up taking 70 years and was not completed until 1928.

Its 20 volumes were published gradually: the first (A and B) in 1884 and the final one (V to Z) in 1928. All the while, people from across the world kept sending in words and quotations, which the editors used as evidence for including a word.

So many people wrote in that Royal Mail had to put a red pillar box outside the house of James Murray, the longest-serving editor, to cope with the volume of his letters in reply

Without these contributions, the dictionary could never have been created. It was one of the first ever crowdsourced projects and it produced the largest English dictionary in the world.

All the slips volunteers sent in – more than two million of them – are stored in hundreds of boxes in the basement of the offices of Oxford University Press (OUP).

I used to work there, as an editor on the OED, and sometimes I would go down into the basement to check on a word and its slips. It is one of my favourite places in the world: quiet, cool, musty-smelling, and full of word-nerd ghosts.

I always wondered how many people had sent in slips, and who they were. We thought there might have been several hundred but, given the number of slips, I suspected there were many more.

Ten years ago, I made a dramatic discovery in the basement that changed how we understand the creation of the dictionary. I took the lid off a dusty box. Inside, I found a small black book tied with cream ribbon.

Opening its crumbling pages, I immediately recognised the immaculate handwriting of James Murray.

I had found the famous editor’s 150-year-old address book with the details of all the people who had sent in words and quotations.

Murray had listed not just the names and addresses of the volunteers, but also every book that each person had read, and the number of slips they had sent in per book. I

It was a key to understanding how the dictionary had been made.

I found a total of six address books, and for the following eight years I worked with a group of students to research every person listed. I wanted to shine a light on them and acknowledge their contribution to this astounding book of scholarship.

3,000 people contributed to the creation of the OED... The remarkable thing about them is that they were largely not the professionals and scholarly elites that you might expect

I call them The Dictionary People, the unsung heroes of the OED, because it could never have been written without them. Entire families were listed in the address books. It is easy to imagine parents and their children sitting around a gas light reading together and writing out slips.

In fact, Murray’s own family also helped in the project. When bundles of slips arrived at Murray’s house, his 11 children would help him sort them alphabetically and file them in pigeon holes. He paid them one penny an hour.

There were so many slips and so many books and papers that Murray’s wife, Ada, asked him to move out of the house. He built a corrugated iron shed in the back garden and grandly named it The Scriptorium.

It was there that Murray wrote the dictionary for the next 35 years. He had dug the shed partially into the ground; it became so dank and cold in winter that he and his fellow editors often had to wrap their legs in newspaper to keep warm.

My research revealed that 3,000 people contributed to the creation of the OED. I tell their story for the first time in my book. The remarkable thing about them is that they were largely not the professionals and scholarly elites that you might expect.

Instead, they were, like Murray himself, amateurs and autodidacts, many of whom had left school at 14 or 15. For them, taking part in this crowdsourced project attached to a prestigious university gave them access to a world they were otherwise denied.

This was a global project with volunteers from India, Australia and Canada, as well as Japan and countries outside the British Empire. We found that there were far more Americans than we’d imagined, and hundreds more women than expected.

A teenager in Calcutta, who eventually became one of the first female archaeologists, sent in Indian English words.

A woman in Philadelphia, who sheltered escaped slaves in her house, sent in the words abolition and abhorrent.

A lesbian couple who wrote poetry together under a male pseudonym sent in thousands of words from the Romantic poets.

Some contributors became obsessed. The top-scoring volunteer sent in 165,000 slips. He became enraged that he was not being paid for his contributions, and was in and out of psychiatric hospitals

Many words relating to sex were sent in by a man living in Bloomsbury, London, who owned the world’s largest collection of pornography.

Three murderers, only one of whom went to prison, contributed in different ways.

And many vicars across England sent in words relating to their favourite hobbies and pastimes, such as wildflowers and stamp collecting, not to mention theology and the Bible.

Some contributors became obsessed. The top-scoring volunteer sent in 165,000 slips. He became enraged that he was not being paid for his contributions, and was in and out of psychiatric hospitals.

In fact, the top four contributors all had connections with asylums, one of whom was hospitalised because of overworking on the dictionary. Was it their madness that drove them to do so much work, or was it the work that drove them mad?

Many vicars across England sent in words relating to their favourite hobbies and pastimes, such as wildflowers and stamp collecting

Not all of The Dictionary People were so conscientious. Murray’s address books are filled with humorous comments beside people’s names. He calls some of them ‘no good’, ‘impostor’ or even ‘hopeless’. Karl Marx’s daughter, Eleanor, fell into this category because she simply copied out words from an existing glossary, making her contributions useless.

Most of the contributors were outsiders, including one called Joseph Wright who started life as a donkey boy in a Yorkshire mine. He could not read or write until the age of 15, but became a professor at Oxford.

His story is told in the chapter in my book called O for Outsiders. There are 26 chapters in total, A to Z, each telling the story of a person or group of people who helped create the OED.

This is a story of ordinary people doing extraordinary things in the name of recording the English language. Many of these devoted volunteers have gone unacknowledged until now.

Without them, the dictionary could never have been written. It is time we gave them credit for their dedication and generosity.

The Dictionary People: the unsung heroes who created the Oxford English Dictionary by Sarah Ogilvie is out in paperback on 5 September (Vintage, £10.99)

Every issue of Saga Magazine is packed with inspirational real-life stories, exclusive celebrity interviews, brain-teasing puzzles and travel inspiration. Plus, expert advice on everything from health and finance to home improvements, to help you enjoy life to the full.

The Bafta-winning actor had been so successful at losing weight, he had to fatten up with a strap-on false belly for his latest role.

The presenter on inspiring the next generation and how daughter Zoe is bouncing back after leaving Radio 2.

The Scottish actor on how he’s still asked to repeat Logan Roy’s most famous catchphrase.

The presenter reveals his surprise contestant and how Richard Osman ‘bullied’ him into writing his debut novel.

The TV adaptation of Rivals has has been judged a rip-roaring success. We caught up with the book's author.

The BBC Radio 4 Today presenter reveals the responsibility and privilege that goes with her job.

The presenter on being sacked by the BBC and why her views are 'career suicide'.

The best-selling author says Pilates has changed her relationship with her body.

Stop smoking, go for a walk and do puzzles, says the veteran newsreader.