A rocky tour - what it's like to work for the Rolling Stones

PR guru Alan Edwards first went on tour with the Rolling Stones in 1982 and reveals all in his new memoir.

PR guru Alan Edwards first went on tour with the Rolling Stones in 1982 and reveals all in his new memoir.

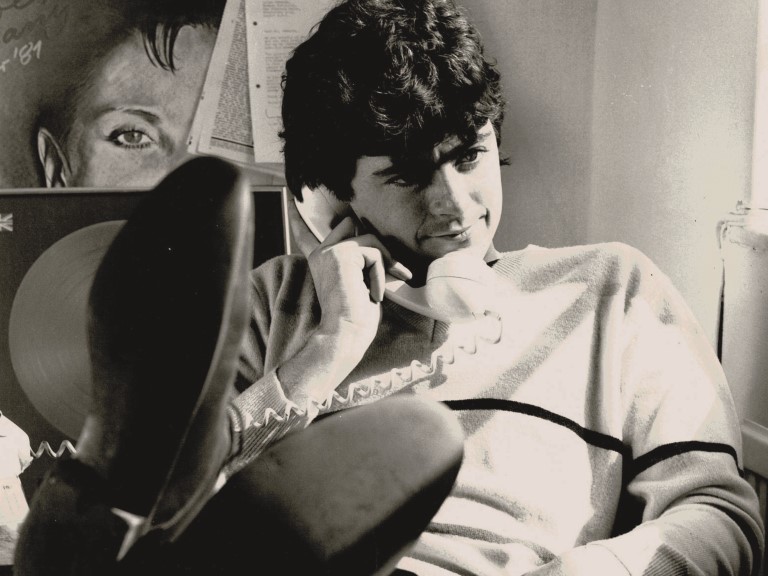

Towards the end of 1981 I received a phone call.

"'Allo, this is ’Arvey," growled the voice at the other end. "Would you be interested in taking on the PR for the Stones?"

There was only one ’Arvey: Harvey Goldsmith, the legendary promoter who practically invented stadium rock in the UK.

And, of course, there was only one Stones.

My answer, obviously, was yes. About a week later, I was summoned to a meeting with Mick Jagger in New York. Mick fired off a volley of questions about the UK music press and nationals, what their circulations were and who owned them.

Next, he started quizzing me on the European media. Fortunately, I had a decent sense of the wider continental press from looking after punk acts.

I swiftly realised that Mick wasn’t so much interested in the actual figures; he just wanted to test my knowledge and see how well I performed under pressure. At the end of the meeting, he gave me no indication of how I had done, but it turned out I must have passed the test – I was hired soon after to manage the media operation for the Stones’ 32-date European tour in June and July of 1982.

Or, at least, I thought I had been hired.

It fast became apparent that Keith Richards had other ideas. I heard from him a few weeks later, when I was sitting in my office at 9pm. The phone rang and an unmistakable, gruff voice said, "Listen ’ere, Sonny Boy Jim. If you want to work with the Rolling Stones, you’ll come and meet me now. I run the Stones, not that f****** poof Mick Jagger."

He told me that if I wanted the job, I had to meet him at a rehearsal studio in Shepperton, a village outside London, at midnight.

I was confused, as I thought I already had the job. I knew where Mick was having dinner – at a swish Italian in Chelsea – so I thought I’d get clarification.

I slipped in quietly and told him what had happened. He looked at me imperiously, said, "Well you’d better go then, hadn’t you?" and kept on eating.

Listen ’ere, Sonny Boy Jim. If you want to work with the Rolling Stones, you’ll come and meet me now

On arrival in Shepperton, I was shown into a tiny room with a broken window, a rusty sink and no chairs. I stood there for hours – the sound of music playing in the distance – until chinks of light appeared under the door and dawn broke.

At about 7.30am, Keith burst into the room, firing a succession of questions at me about blues and reggae – both things, luckily, I knew a lot about.

He was intense, yet strangely relaxed, and all he wanted to talk about was music. I guess he was just sizing me up and teaching me a bit of a lesson.

The conversation lasted about 15 minutes and then he simply departed. It was becoming clear Mick was the business mind and Keith was the music brain, and they’d both tested my wits and willing in their own ways.

A few days later the band’s business manager confirmed I’d been hired for £150 a week.

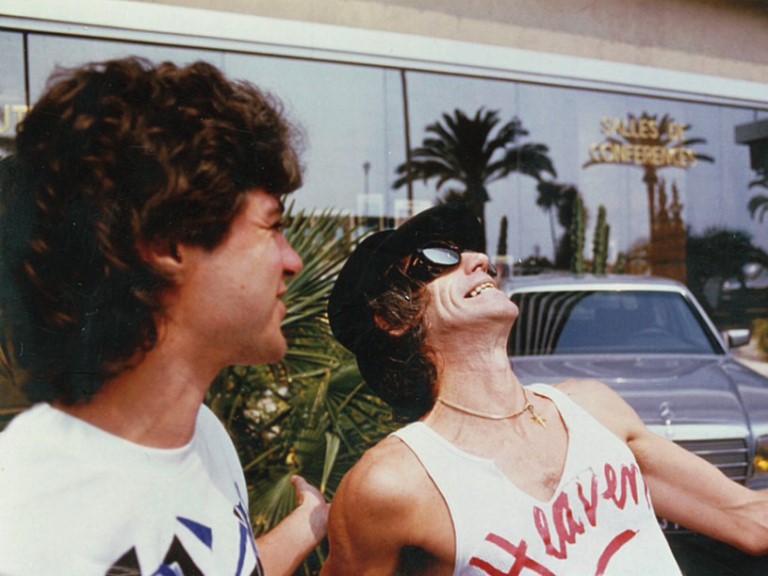

Fast forward to May 1982 and we were heading off on tour. The Stones were travelling on their own 747 jet, an unimaginable luxury compared with the cramped tour buses I was accustomed to.

The plane, complete with glamorous hostesses, was more like an ocean-going cruise liner, as opulent as you could imagine – white leather seats and endless fine food and drink.

One time, the tour manager couldn’t wake Keith up in a hotel room to fly to the next country, so roadies carried the bed, with Keith sleeping in it, out of the hotel, loaded it onto the plane and then hauled it off when the aircraft touched down. Keith woke up in another hotel room in another country without even having stirred.

It was becoming clear Mick was the business mind and Keith was the music brain

Soon I was getting to grips with the reality of life on the road with the Stones, which basically consisted of running up and down hotel corridors checking whether members of the band were ready for interviews, while at the same time trying to placate frustrated journalists waiting downstairs who were worried that their interviews weren’t going to materialise.

Now I understood why Mick had to keep so fit; the tour was about stamina as much as anything.

Mick and Keith, in their own very different ways, knew how to give good copy. The only member of the band who wasn’t the slightest bit interested in publicity was drummer Charlie Watts. I only ever managed to get him to do one press interview, and that was talking about upcoming Test matches with The Daily Telegraph cricket correspondent.

The tour was well received but never mind the 19th Nervous Breakdown, I started to worry if the intense pressure might give me my first. The band members wanted a report under their door each morning, including reviews of the previous night and the schedule of media to be done that day.

Some days I found myself running alongside Mick on his morning jog, reading him the previous day’s press clippings.

Working for the Stones was exciting, yes, but very intense. I was just 27 years old and absolutely exhausted.

Although I liked to think I got on with the band, I wasn’t their friend. The world of the Stones was full of intrigue and politics; it was a bit like a medieval royal court with everyone jostling for influence and favour.

Mick and Keith were going through a period of open warfare about their prospective solo careers and were barely on speaking terms. By the time I got caught in the crossfire, they were conducting much of their dialogue through the front pages of the tabloids.

Needless to say, much of my time was spent undertaking crisis management, responding to Mick’s outbursts, feeding them back to Keith and vice versa.

Arguments often got nasty but I now realise that the broader power struggle between Mick and Keith was really just a way for them to amuse themselves. It was like they were playing ping-pong with various personnel on the tour to see what would happen. I definitely started to feel like a pawn in the game and soon became aware of just how expendable I was.

The world of the Stones was full of intrigue and politics; it was a bit like a medieval royal court with everyone jostling for influence and favour

And then towards the end of the tour I was fired. I still have no idea why.

I’d turned up after the concert in Vienna on 3 July to a deserted airfield near the city. It was about midnight and, as usual, everyone had their cases and baggage in hand as we climbed the stairs to find our allocated seats. However, when I got to mine, I discovered someone else sitting in it.

There were a few smirks, and general avoidance of eye contact, but nobody said a word. I sensed quickly that this was Mick’s idea of telling me I was surplus to requirements.

I had been embarrassed and, of course, I was hurt, but there wasn’t much I could do about it because the plane was about to leave.

I found myself back on the runway. It was like the final scene in Casablanca: I stood there holding a cheap suitcase as the airliner thundered off into the sky. Tears welled; I just wanted to get back to the UK.

The one thing they hadn’t thought of was to confiscate my all-access pass, which remained safely around my neck during the whole miserable episode. I knew that if I turned up at a gig, the security would let me backstage.

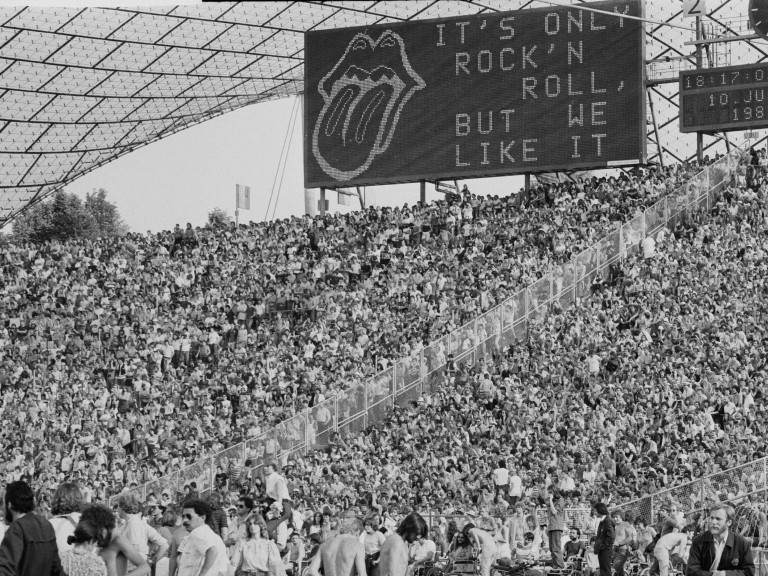

I’d seen my chance to brazen things out and got an overnight train to Cologne in Germany, the venue for the next two concerts. I arrived at the Müngersdorfer Stadion and walked around all day, cheerfully acting as if nothing had happened, fulfilling as many of my duties as was practical.

Everyone was too embarrassed to say anything. I did the same thing again the next day, carrying on as if oblivious to the fact I’d been fired.

After a third day of this charade, Mick walked over to me. "Oh, all right," he said. "You can have your f****** job back then."

He sashayed off as only he could. I’d go on to work with the Stones for several more years alongside my other clients and Mick’s role in my life would continue for far longer.

After my youngest daughter was born in 1987 I happened to be at Mick’s and mentioned that my wife Valerie and I were scratching our heads for an appropriate name.

"Well, it’s Tuesday, innit?" he said. "Why not call her Ruby?", referencing one of their biggest hits.

And that was how my youngest daughter came to be named.

Alan Edwards is the founder of PR agency Outside Organisation. His book 'I was there: Dispatches from a Life in Rock and Roll' is out now RRP £25, published by Simon & Schuster UK

.jpg?la=en&h=541&w=1232&hash=68EDA28677DE015BF53916AA57CAD1F7)

For the Bake Off judge, the funniest festive season was the one when the lunch went completely wrong.

The actor bids farewell to Downton and looks forward to his starring role in a new West End show.

The TV historian on overcoming a difficult childhood and what it was like to appear on Celebrity Traitors.

TV’s Dr Hilary Jones on why he wants sweeping reform to modern healthcare.

The wildlife filmmaker on his close call with a polar bear and why hanging out with big cats is less scary than driving.

The Irish author, 62, on escaping the news through writing, staying sober and scrolling the internet for pretty things.