Can you hear the hum?

For almost 50 years, people across the UK have reported hearing a low pitch droning noise. It's now the subject of a new BBC drama, but what is it?

For almost 50 years, people across the UK have reported hearing a low pitch droning noise. It's now the subject of a new BBC drama, but what is it?

Yvonne Conner was in her living room one evening in March 2020 when she first heard a humming sound, like a plane circling overhead. She asked her husband Mark if he had heard it too.

"Heard what?" was his response.

Nonetheless, as days passed, Yvonne heard the hum everywhere. It was loudest in the evenings, inside her four-bedroom stone terraced home in Holmfield, West Yorkshire, but she heard it outdoors too, within a five-mile radius of the town.

She pressed her ear to the walls, turned the electricity off and asked her neighbour if they’d moved their washing machine, all to try to pinpoint its source.

"I’d get in my car at 11.30pm and trawl the streets listening to air-conditioning units," says Yvonne, 53, who set up a Facebook page called The Hum to collate reports.

Although other Holmfield residents heard it too, as – eventually – did Mark, it bothered few as much as it did Yvonne.

"I felt I was being tortured every night in my own home. It’s always there," she says.

Last night she was awake until 5am, the white noise she plays on the Alexa speaker by her bed incapable of drowning out the sound.

Over the years, hums have been attributed to everything from aliens to the start of the apocalypse

Where does it come from? That's the question that haunts Yvonne, and haunts thousands like her who hear what’s known as the worldwide global hum – a persistent, unidentifiable low-pitched noise.

It is thought as many as 4% of the world's population is plagued by this persistent noise - described as similar to the sound of a lorry or large truck idling nearby.

The first known hum was heard in Bristol in the 1970s, reported to a newspaper by 800 residents and so bad it apparently caused a few nosebleeds. There have since been reports in dozens of locations, from Germany to New Mexico, although the bulk of cases seem to be in England and North America.

In 2014, residents of Surbiton, south-west London, were handed noise diaries by their council to track what one said was a "whirling motor sound".

In the past year, people in Immingham, Lincolnshire, have been kept awake by a hum that is described by resident Christine Neilson, 74, as "very uncomfortable on the ears". One man has resorted to driving around the town in his dressing gown trying to find its source.

In British Columbia, Canada, science teacher Dr Glen MacPherson first heard a hum in his coastal town at 10pm one evening in 2012.

"‘I assumed there were float planes overhead but after the third or fourth night that didn’t make a lot of sense," he says.

He unplugged his fridge and turned the electricity off at the mains, but the hum got louder. Although he heard no hum outside, he heard it inside his car, with the engine off and windows up.

"It was a fully-fledged mystery,’ says Dr MacPherson, who googled low frequency humming noise but found only "conspiracy and lunacy", as he puts it. Over the years, hums have been attributed to everything from aliens to the start of the apocalypse.

It’s not unheard of that people claim to hear hums that nobody else around them can verify

"What was needed was a serious scientific inquiry," he says.

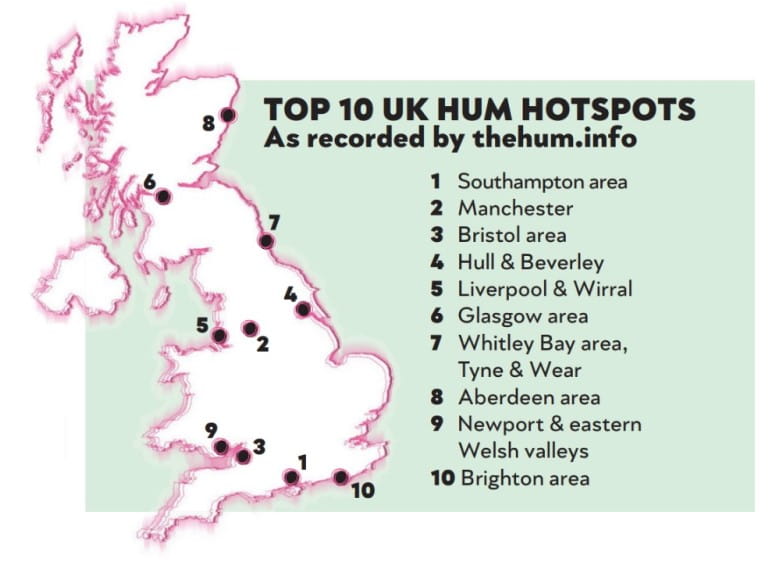

Dr MacPherson launched a worldwide database (thehum.info) for people to report hums and fill in a questionnaire.

(Does the sound change with the weather? Is it masked by background noise? Have you been diagnosed with vertigo?)

He now has nearly 10,000 hums on his map. There is no average age or gender for those who hear them, but those with a family history of ADHD or autism are ‘over-represented’ – as are, bizarrely, the ambidextrous.

There are clusters in cities but plenty in rural areas too. Dr MacPherson first thought the culprit might be radio waves used by military powers – a theory floated by geoscientist David Deming in 2004. He built a big metal box that radio frequencies wouldn’t be able to penetrate: "Once inside, for a few of us the hum got louder, so we set that theory aside."

Now he believes the most reasonable explanation is that it isn’t a sound in the usual sense of the word, but internally generated by some interaction between the human auditory system and brain. One current theory he’s looking into is that some people’s hearing might be affected by medication.

"Perhaps there was an over-the-counter or prescription medication that first appeared in England when the hum started and came to America not long afterwards, that is known to be damaging or disruptive to the auditory system.

"It turns out there is one," he says, hesitantly, for fear, perhaps, of being accused of scaremongering, "…and that’s good old ibuprofen."

I felt I was being tortured every night in my own home. It’s always there.

It’s true that frequent use of ibuprofen and other anti-inflammatories has been linked to a higher risk of tinnitus, but that’s as far as it goes. There are other potential explanations related to our hearing, says Dr Matthew Barnard, an expert in acoustics from the University of Hull.

"There’s a phenomenon called otoacoustics, which is when your hearing mechanism makes very subtle noises," he says.

Then there is misophonia – a decreased emotional tolerance or hatred of certain sounds. A study suggested that around 18% of the UK population could be sufferers.

Dr Barnard thinks it a safe bet that the hum is anthropogenic – caused by human activity, be it from power generation or pipework – but says what each of us hears can still be a personalised thing.

"It’s not unheard of that people claim to hear hums that nobody else around them can verify," he points out.

Which can lead to ridicule for sufferers: "I’ve had Facebook posts telling me, 'You’ve got your vibrator on too high, love'," says Yvonne, whose hearing has been declared perfect by a specialist.

She is convinced the Holmfield hum comes from machinery in local factories, which was upgraded in 2020. Yet in October 2022 Calderdale Council closed the two-year investigation she had petitioned them to start after amassing 500 signatures, claiming it was unable to identify the source.

"I was fuming," says Yvonne, who had to leave her job because of exhaustion and is now a dog walker.

Mark, 62, has been supportive, but she says, "it was starting to put a strain on our relationship. He was happy to put up with it [the noise]. I was frustrated with it."

When clusters of people report a hum in the same area, Dr MacPherson believes these are likely to be anthropogenic sounds rather than individual auditory problems. But they’re still likely to be audible only to those with sensitive hearing. To further complicate matters, anthropogenic sound might only become a hum when it enters a home.

"Essentially, sound is just vibration in a medium," Dr Barnard explains, and vibrations caused underground by a pipe network at a low frequency, for example, could hit brickwork or steel framing causing ‘harmonics’, which can be four times the frequency of the original source.

Sound is measured in hertz, with one hertz equal to one vibration per second. Dr Barnard says hums could vary between 80 and 200 hertz; when Yvonne measured hers with an app on her phone it spiked at 105.

Everyone has a right to peace and quiet in their own home

Some experts, such as the late audiologist David Baguley, have claimed anxiety about the hum exacerbates it, essentially because the body responds by amplifying the sound. It’s a theory Dr MacPherson describes as mildly insulting.

"For some people, there’s genuine suffering," he says.

One of the reasons the hum is so torturous is its monotony, says Dr Barnard. "It’s unnatural, it’s sustained and as a result inescapable. It becomes this pervasive all-encompassing sound, almost threatening – invisible but everywhere. Once you've noticed these sorts of things it's very hard to tune out."

Dr MacPherson has found that living with background noise seems to help.

"Around 2016, I moved into the forest and the hum absolutely roared. But now I’m close to a main [road] I haven’t heard it in quite some time."

For Yvonne, sadly, the hum remains. She considered selling her house. "But why should I? Everyone has a right to peace and quiet in their own home."

For a limited time, enjoy 3 issues of Saga Magazine for just £1. Receive the next 3 print editions delivered direct to your door, plus 3 months’ unlimited access to the Saga Magazine app—perfect for reading on the go.

Don’t miss your chance to experience award-winning content at an exceptional price.

Women in the intelligence services did more than just take notes and chide flirtatious spies - many had real power and ran missions.

Anne Robinson on what to say when you read a friend's book and it's terrible.

Anne Robinson helps a man who thinks his life doesn't feel important after retirement, and asks how to find purpose again.

Dr Miriam Stoppard advises a widow on how to navigate modern dating etiquette and broaching the subject with her grown-up children.

Our columnist on the challenge of making a will and whether we should instead be spending our money on ourselves.

Self-publishing is becoming popular among older authors who want more creative control – and a bigger slice of the profits.