Meet the tunnel rats of Ramsgate

Memories of the remarkable network of air-raid shelter tunnels that saved hundreds of lives during WW2.

Memories of the remarkable network of air-raid shelter tunnels that saved hundreds of lives during WW2.

On a bright, breezy morning in the Kent resort of Ramsgate, 15 pensioners sit enjoying the sunshine, chatting over coffee and cake.

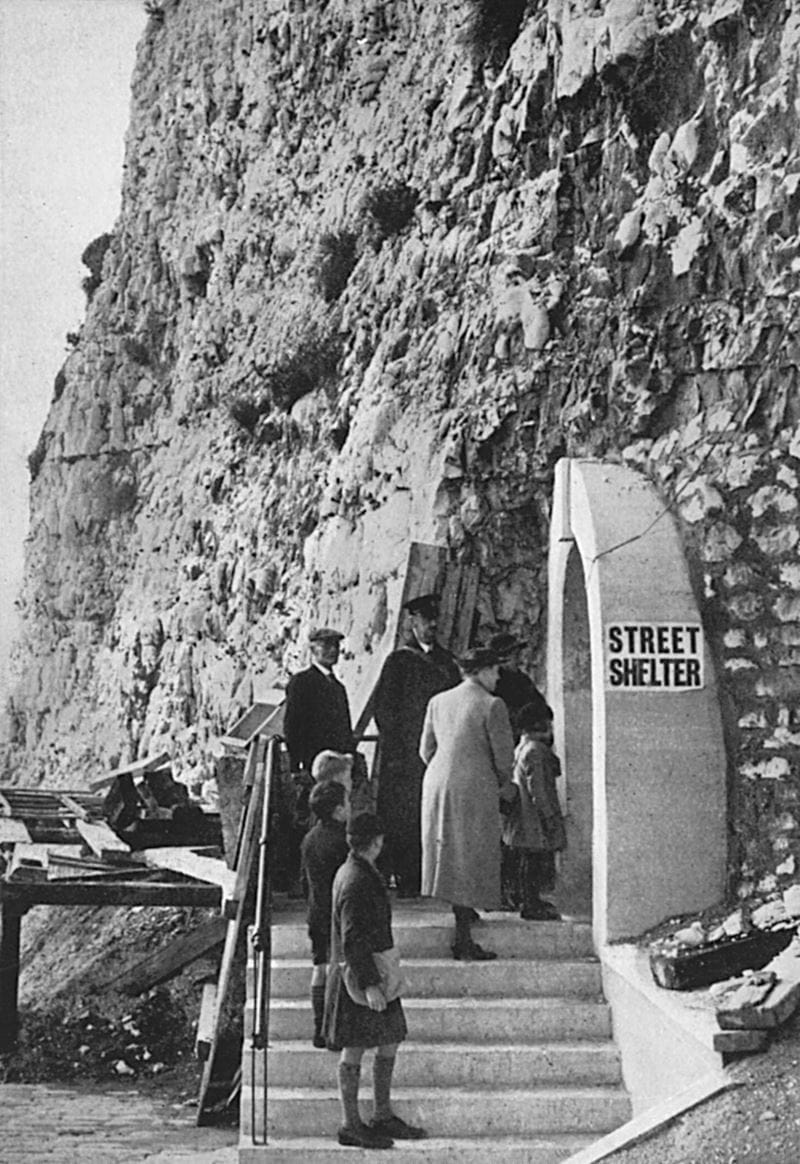

Beside them is the portal to the UK’s largest system of air-raid precautionary (ARP) tunnels – reimagined as a visitor attraction, gallery, museum and café – to which thousands owe their very existence.

Men swap stories of wartime escapades – of playing on bombsites, clambering on Bofor anti-aircraft guns and watching ‘dogfights’ overhead.

They regale each other with tales of how, as pesky schoolboys, after the war when the tunnels were closed, they would find ways to sneak into their great subterranean adventure playground.

Meet the Tunnel Rats, a club for people born or raised in Ramsgate in the Second World War.

With some 22 members aged from 80 to 93, the club was born after a Ramsgate Tunnels Veterans Reunion in March 2022, reclaiming a nickname bestowed on them by exasperated adults.

The story of Ramsgate Tunnels begins in 1938, with borough engineer Richard Brimmell, supported by mayor Arthur Kempe, at work on plans for a network of deep shelters to be hewn out of Ramsgate’s chalk foundations.

The two foresaw that the town, overlooking the English Channel and just Spitfire seconds from RAF Manston, would soon be Bomb Alley.

Brimmell’s scheme envisaged a 31/4-mile semi-circle linking into a Victorian railway tunnel, ensuring no one would be more than five minutes from an entrance.

As many as 60,000 people would be able to take refuge, with electric lighting, signage, canteens, chemical toilets, cold water, benches and bunks available.

The first section was opened by the Duke of Kent on 1 June 1939.

On 3 September, war was declared, and in May 1940, Ramsgate schools were evacuated, with 3,255 pupils sent to Stafford.

With the schools closed, the town would have felt like Hamelin after the Pied Piper departed, but for a small number of children who stayed behind.

Ethel Horsley, 89, was one of them. Her brother, David, three years her senior, had died just before the war, of diphtheria and meningitis, and her parents couldn’t bear to part with little Ethel.

She remembers with a shudder 24 August 1940, when 500 bombs dropped on the town, while people were strafed with machine-gun fire.

Although 1,200 homes were destroyed, only 29 civilians and two soldiers were killed, thanks in great part to the tunnels.

"It was a beautiful day," says Ethel, who was almost six at the time.

"We were in the garden when we heard the drone of aircraft. We just stood there staring at what looked like a swarm of bees, and as they came closer, we could see the iron crosses painted on them. Then the bomb doors opened, and the bombs started falling."

The bombing was over in five minutes but then there were fires to contend with. Ethel’s dad, who had been gassed on the Somme, was with the Auxiliary Fire Service, and fought the blazes.

The smoke played havoc with his ruined lungs, and he had to stand down after that day.

Determined to carry on helping his country, he volunteered as a Civil Defence Warden when he had sufficiently recovered.

Community stalwarts, the wardens offered guidance and leadership to the public, regularly working nights.

"When he was on nights, he couldn’t bear the thought of coming home in the morning and finding us gone," says Ethel.

So at 9pm, Ethel, her sister Olive, 19, and their mum descended the tunnels to their bunks, where they kept eiderdowns and pillows, and slept in their clothes, returning home at 6am.

It was safe but not salubrious.

"It was cold, damp and smelly. We were right opposite a toilet. One night a drunk fell into my bunk," she recalls.

The tunnels, meanwhile, had begun to resemble a "town beneath the town", as 300 homeless families took up residence.

They erected screens, brought down clocks, pots and pans, ornaments – even gave their makeshift abodes a name or number.

There was a barber, first-aiders, greengrocers, parties.

Life underground is evoked in the memoir, A Ramsgate Boy’s Memory of the Second Word War, written by Denis Rose before his death in 2001.

"We had an alcove. It was about 8ft by 6ft… and two sets of bunk beds… We had Valor stoves to cook on and lived mainly on stews… Saturdays were party nights, with dancing and singing. Even in the times of despair there were some highlights."

"But always there was fear – particularly of the flying bombs, known as ‘doodlebugs’. You’d hear the drone, an ominous silence then the crash as the engines cut out and they dropped.

"The Spitfires would fly alongside them and try to tip them into the sea," says Brian Woodland, 88, a volunteer tunnels guide.

Brian makes short work of a flight of 144 stairs, leading down to the tunnels at the deepest point.

Poor Ethel once took a tumble down these same stairs when, reaching the top one frosty morning, she was distracted by the sight of a Hurricane chasing a Messerschmidt, as German bullets grazed the threshold.

Today, back pain serves as a reminder. Brian’s father was a fireman, facing awful risks.

When the sirens sounded, Brian would grab his red Mickey Mouse gas mask and be led to the nearby tunnels entrance.

"Mum and Dad used to take us down. I can remember seeing all the people living down there. But, once the all-clear went, we’d go back out and home again."

Was he ever terrified?

"At nights, when the guns were firing and the searchlights were shining, I used to wake up crying, but beyond that, no, it was just an adventure."

While Brian and his younger brother were sent for a while to relatives in Hertfordshire, Joyce Battery, 93, and her little brother, stayed put.

"My mum wouldn’t let us be evacuated, because Dad was abroad with the Air Force, and she didn’t want to split the family up more."

After school resumed in 1941, Joyce would be taken into the tunnels with her classmates, but her mum was a tunnels sceptic.

"She didn’t want to go down there. She was a bit naive, I imagine. She just believed if your number was on [a bomb], you’d get it. Yet the tunnels saved so many lives."

I ask about their memories of VE Day. For the then nine-year-old Ethel, it was a time of sadness, as her father’s health failed.

"I think we were just so relieved, but more concerned with the people who were sick."

Brian, meanwhile, remembers a street party ("just a small affair"), and movie newsreels – "Churchill, Buckingham Palace, the march past, the flypast…" he recalls.

For Joyce, by then 13, VE Day was a time of much excitement.

"My father was in India, and I thought, 'Dad will soon be home'," she says, "but it was August before he came back."

We think of delirious, cheering crowds, of people frolicking in Trafalgar Square fountains, but in Kent’s ‘Hellfire Corner’ it was not one big knees-up.

This was not unusual. A sad, reflective mood was common, according to University of Exeter historian Professor Richard Overy.

"People wanted normal life to return, but they didn’t know when their loved ones serving in the Armed Forces would return… Others had experienced terrible losses. The end of the war was a difficult period of transition for many."

All the same, 8 May will be a day of fun, with the tunnels rocking to the sound of jazz and swing band Hullabaloo. Then, from 17 May, there will be more celebrations for what Churchill called 'a miracle of deliverance’.

It was from Ramsgate that the 850 ‘Little Ships’ – the most raggle-taggle armada in all history – sailed to the aid of Allied troops on the beaches of Dunkirk between 26 May and 4 June 1940, helping to rescue more than 336,000 trapped British, French and Belgian soldiers.

The townsfolk turned out to welcome survivors, kettles were boiled, sandwiches cut. Joyce recalls watching shattered, dishevelled men come ashore, wrapped in blankets.

This year, more than 70 of these cherished vessels will arrive in Britain’s only Royal Harbour, in preparation for a return crossing on 21 May (see adls.org.uk).

It will be a stirring sight and another memorable day for this small town with a very big history. Just ask any rat.

For a limited time, enjoy 3 issues of Saga Magazine for just £1. Receive the next 3 print editions delivered direct to your door, plus 3 months’ unlimited access to the Saga Magazine app—perfect for reading on the go.

Don’t miss your chance to experience award-winning content at an exceptional price.

The ultimate guide to Saga Puzzles, full of technical tips, tricks and hints.

With the start of the new financial year on 6 April, our money expert explains the changes to your pension, benefits and taxes.