Health & Wellbeing

Our experts show you simple and effective ways to stay healthy and active, so you can live your passions every day.

Vitamin D: are you taking the right kind?

We explain the difference between D2 and D3 and if a higher dose is always better.

The 7 signs you need a new pillow

Sleep experts say a worn out pillow could be sabotaging your sleep.

RSV vaccine: over 80s can finally get their free jab

At last – people over 80 are eligible for the RSV vaccine after a government change of heart.

How I helped rebuild my mum and dad

Rhoda and Michael Stephen were facing increasing ailments and a lack of mobility in their eighties. Until they took up weightlifting.

How our brains change at 66 and 83

We examine the science and how to best look after our brain as we get older.

I tried fermented food for a month and this is what happened

Is eating fermented good for you? Our writer gave it a go for four weeks, with some mixed results.

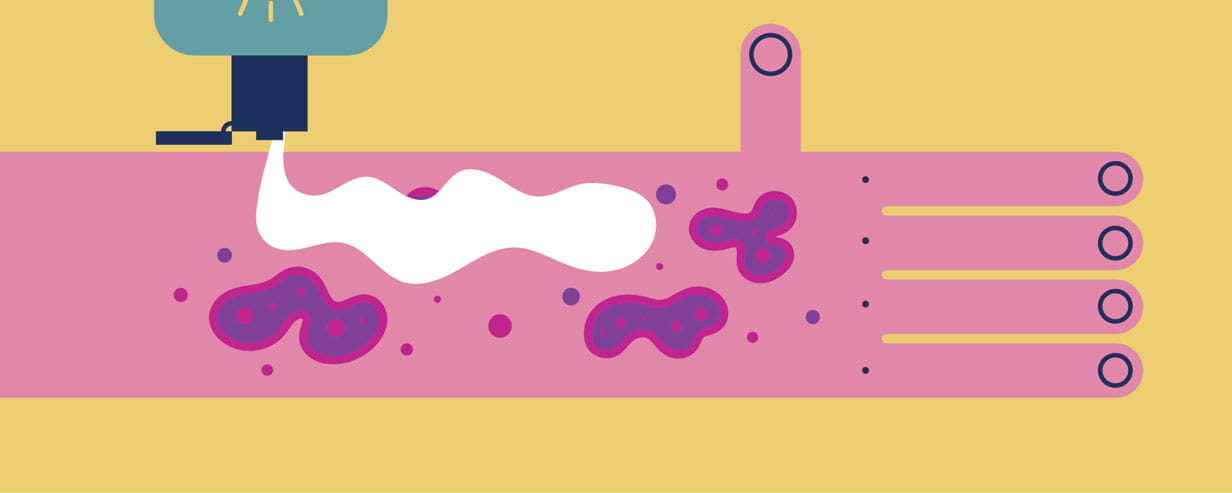

Do dogs make you healthier? A world-leading gut expert thinks so

Tim Spector explains how dogs support our gut health.

Which tinned fruit is best for your health - and which to avoid

Why am I bruising so easily now I'm older?

Dr Mark Porter advises on senile purpura, a type of bruising that is common as we age.

14 simple habits that could transform your life this year

We asked the experts for the small changes that can have the biggest impact on our health, mood and resilience.

Vitamin D: are you taking the right kind?

We explain the difference between D2 and D3 and if a higher dose is always better.

I tried fermented food for a month and this is what happened

Is eating fermented good for you? Our writer gave it a go for four weeks, with some mixed results.

10 things you might not realise your pharmacist can do

Your neighbourhood pharmacist now offers a surprising number of services.

Heart valve disease is on the rise. Here’s all you need to know

We share the warning signs and examine the treatments available.

For a limited time, enjoy 3 issues of Saga Magazine for just £1. Receive the next 3 print editions delivered direct to your door, plus 3 months’ unlimited access to the Saga Magazine app—perfect for reading on the go.

Don’t miss your chance to experience award-winning content at an exceptional price.

Play our free daily puzzles

Beat the boredom and exercise your mind with our selection of free puzzles.