Why lab-grown diamonds may become everyone’s best friend

Sales of lab-grown diamonds are on the rise – they are cheaper and more ethical than mined ones, but are they as precious?

Sales of lab-grown diamonds are on the rise – they are cheaper and more ethical than mined ones, but are they as precious?

Diamonds are forever, at least that’s what we’ve believed for the past 77 years since De Beers, one of the world’s largest diamond companies, propagated that slogan and made billions in the process.

They’re a girl’s best friend, too. And they’re the engagement or Valentine’s stone, symbolising eternal love, with prices to match that status.

Yet the exclusive diamond industry is now riven with magma-hot tensions. Dazzling rocks formed over billions of years in the depths of the earth have a rival in the form of equally sparkly lab-grown – or synthetic – diamonds, made in weeks.

Both are ranked as diamonds by the International Gemological Institute but buyers are going wild for the second, cheaper version.

“This is the industry topic of the moment,” says gemmologist Helen Dimmick.

“Lab-grown diamonds are not fakes, they are physically, chemically and optically the same as natural diamonds. You can’t tell the difference with a jeweller’s loupe, the only way is to use a special machine that detects growth patterns.”

Production methods apart, there’s a key difference between the two: cost. With rapidly improving technology, prices for lab-grown diamonds are continually dropping – they’re now selling for between 33% and 80% less than their mined equivalents.

Figures show that lab-grown accounted for 18.5% of diamond jewellery sales in 2023 internationally, and it’s still growing. The industry is worth more than £23bn worldwide.

Unsurprisingly in a cost-of-living crisis, sales of natural diamonds are down more than 50% as customers realise they can buy a mined diamond’s twin and still have change for a fabulous holiday.

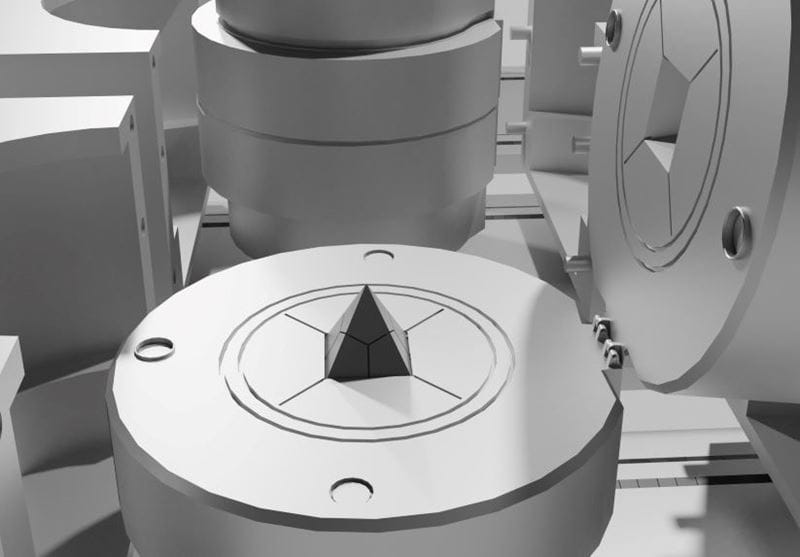

First designed by scientists at General Electric in 1954, the high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) method involves placing a “seed” (diamond chip) inside a press, along with a metal catalyst, under a block of carbon.

The press heats the cell up to 1,600°C. The metal melts, and it carries carbon atoms from the graphite to the seed crystal, forming a diamond within weeks that can be styled and polished.

In a second method, called chemical vapour deposition (CVD), the chip is placed in a vacuum chamber filled with carbon-heavy gases, heated to 1,000°C to turn into plasma. This then bonds with the diamond slice and builds the finished diamond in layers.

“I find looking at the definition adopted by the industry really helps – a gemstone is rare, durable and beautiful,” Dimmick says. “Lab-grown diamonds are still the strongest, hardest material known to man. They’re incredibly beautiful with their fire, brilliance and scintillation, but they are not rare.

“When we think of love we think of something that’s durable and beautiful, and when something’s also rare it becomes the ultimate symbol of that. A lab-grown diamond is more of a technological phenomenon.”

Yet many dismiss the idea of mined diamonds’ rarity as a myth perpetuated by the industry to stimulate desire.

From its inception in 1888 until the early 21st century, De Beers controlled around 85% of the world’s diamond supply. It purposefully held back stones to create demand.

“Diamonds are beautiful but not scarce, they are the most ubiquitous and plentiful precious gemstone on the planet, we get better at mining them every day and a huge amount are coming out of the ground,” says Aja Raden, author of Stoned: Jewelry, Obsession and How Desire Shapes the World.

“Making people think they are running out is just a way of making them more desirable.”

Price isn’t the only influencing factor. Many love the ecological credentials of lab-growns, with A-listers such as Lady Gaga and Rihanna – who could both easily afford naturals – spotted wearing them.

Mining causes deforestation and erosion, with toxic chemicals dumped or leaked into soil and waterways. The average diamond has an estimated footprint of 57kg of CO₂ per carat – for a lab-grown it’s around 0.028g.

With the price of gold near an all-time high, now could be a good time to consider selling any gold which you don’t wear and which hasn’t got sentimental value.

Saga Money has more on how to get the best price for it and the mistakes to avoid.

Increasingly, consumers have ethical concerns too: a 2018 Human Rights Watch report found forced labour and child labour, plus dangerous work practices, ongoing in much of the industry in Africa. And then there’s the association with “blood diamonds” – gems obtained through terrible human rights abuses used to fund guerrilla warfare.

“This is not going to cut it when brilliant alternatives are available,” says Rowan Aplin of Lily Arkwright, which sells lab-grown gems in London and Manchester.

Yet natural diamond traders say that the Kimberley Process certification scheme – introduced in 2003 to stop conflict diamonds entering the mainstream – has cleaned up the business, the Natural Diamond Council adding that mining has transformed the economies of countries such as Botswana, Namibia and South Africa.

Worldwide it is thought that ten million people work in the industry supporting an estimated 45 million family members. Natural diamond traders also point out that 56% of synthetic diamonds are grown in China, followed by 15% in India – countries with often poor records in workers’ rights and environmental practices.

“Sustainability is a false narrative,” insists gemmologist Julia Griffiths. “Only a very few companies think about this issue, for most it’s just another mass-produced product.”

Jessica Warch, of Kimai Jewellers, whose diamond earrings – from a lab in India – have been worn by the Duchess of Sussex, agrees that you have to investigate the origins of synthetic diamonds.

“We try to work with labs using renewable energy and we’re not leaving huge holes under the Earth to get a piece of stone on your finger, which is really important to us,” says Warch. “The key if you’re buying a lab-grown stone is to ask the right questions.”

Warch founded her brand after watching the industry fail to evolve.

“There’d been no change in the past 100 years on traceability,” she says.

“A diamond often exchanges hands over 20 times after being mined, making it almost impossible to know where it came from and under what conditions it was pulled from the Earth.”

In the early days, Warch met hostility from the natural industry, horrified at this threat to its business. “The press would say, ‘We love what you’re doing, but we can’t publicise it because then the big players won’t advertise with us’.”

Australian gemologist Steve Richards told the Guardian in January 2025: “I’m a gemologist and a diamond technologist and I’ve been doing it for 30 years and if you put one next to the other I wouldn’t have a freakin’ clue which is lab grown.

“I wouldn’t buy mined diamonds again. You’re wasting your money.”

But that’s changing as big jewellery companies acknowledge how the wind’s blowing. A 2022 survey of 1,200 consumers in six countries found that 61% would choose an identical lab-grown diamond ring priced at £3,900 over the 26% who would opt for an identical £5,500 mined alternative.

And, in 2021, the world’s biggest jeweller, Pandora, announced it was stopping selling mined diamonds to focus on lab-growns made with 100% renewable energy in the US.

Even De Beers, which had previously marketed its Lightbox selection of lab-grown jewellery as purely for frivolous occasions, last year extended the range to include the engagement market.

Jewellers say customers aren’t spending less on lab-grown engagement rings – instead they’re using the same budget to go bigger, inspired by images of celebrities sporting lab-grown jewels, sometimes as vast as 12 carats.

“People are now opting for maybe 1.5 to two-carat oval rings whereas before a one-carat round diamond was a bit of a status symbol,” confirms Aplin.

Yet young couples are not the only lab-grown fans. “I’ve had customers in their late 70s who want huge diamond earrings, for example, and realise they can afford to treat themselves to lab-grown and they don’t care about resale value,” says Dimmick.

Synthetic or natural, we’ll never stop loving jewellery.

“Everyone is transfixed by sparkles,” says Raden. “Parts of our brain that have existed since before we were mammals associate sparkles with water and think, ‘I have to have this’.”

Natural diamonds may not be forever, but the lure of something glittery will survive.

It’s a good idea to have home insurance jewellery cover for items of significant value such as engagement and wedding rings, anniversary gifts, luxury watches and heirloom jewellery.

Check the single-item limit when buying your contents insurance as anything above that amount will need to be listed separately. Saga insurance experts have more information.

Whether you're looking for straightforward insurance or cover that's packed with extras, our home insurance has plenty of options for people over 50.

With our Stocks & Shares ISA and General Investment Accounts. Capital at risk.

The ultimate guide to Saga Puzzles, full of technical tips, tricks and hints.

With the start of the new financial year on 6 April, our money expert explains the changes to your pension, benefits and taxes.