Entertainment

Fun ways to pass the time, including TV reviews, ideas for days out, and interviews with top celebrities.

Prue Leith on Bake Off and learning to love being old

Dame Prue Leith talks about her secret to staying young and why she’s finally slowing down at 86.

The Saga Magazine March pub quiz - A poet, a playwright and a Plantagenet king

Put your general knowledge to the test with our 20 brain-teasers.

Adjoa Andoh on her Bridgerton future and being a famous grandma

The actress opens up to Jenni Murray on Saga's podcast Experience is Everything.

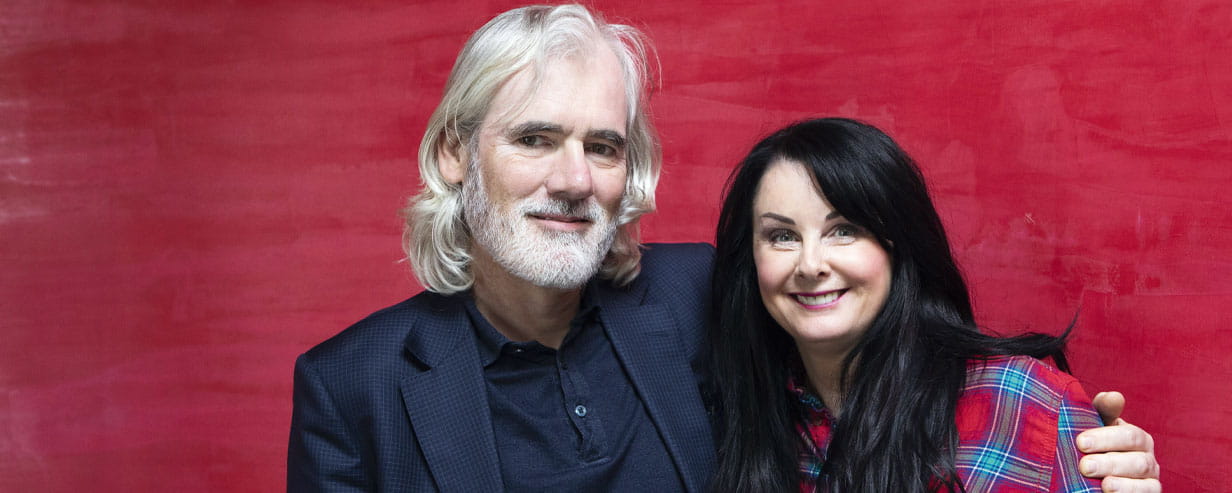

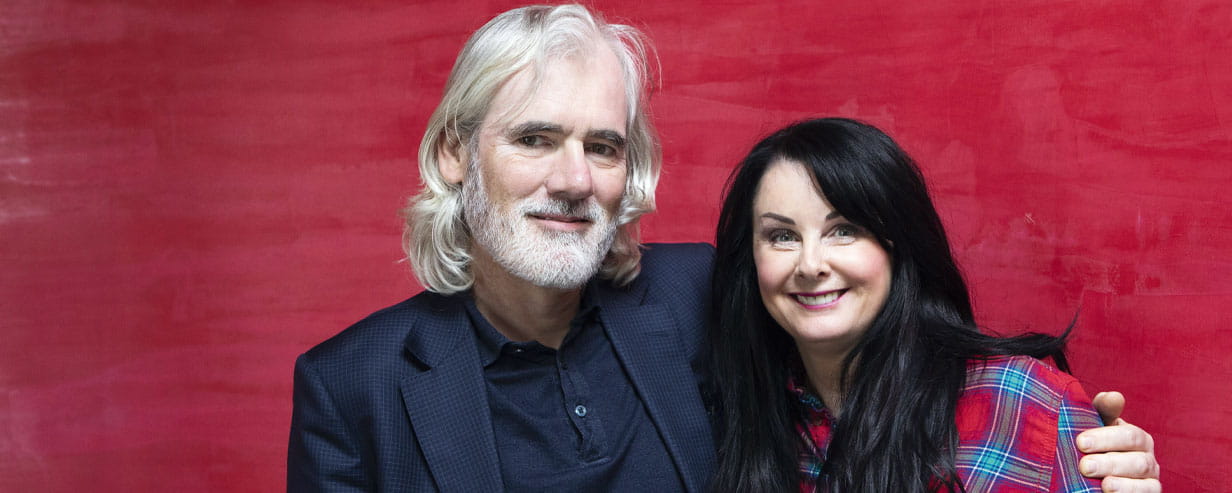

Marian Keyes on staying sober and online scrolling

The Irish author, 62, on escaping the news through writing, staying sober and scrolling the internet for pretty things.

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry review

Both a show that will make you cry and a musical that will make your heart sing.

David Olusoga on his extraordinary mum and The Celebrity Traitors

The TV historian on overcoming a difficult childhood and what it was like to appear on Celebrity Traitors.

What to read in March - our choice of the best new books this month

From the Australian Outback to Imperial Russia, families loom large in this month’s reads – plus murder most twisty.

Paul McCartney on Lennon, Linda and life after The Beatles

We spend an evening with music icon ahead of the release of his new documentary, Man on the Run.

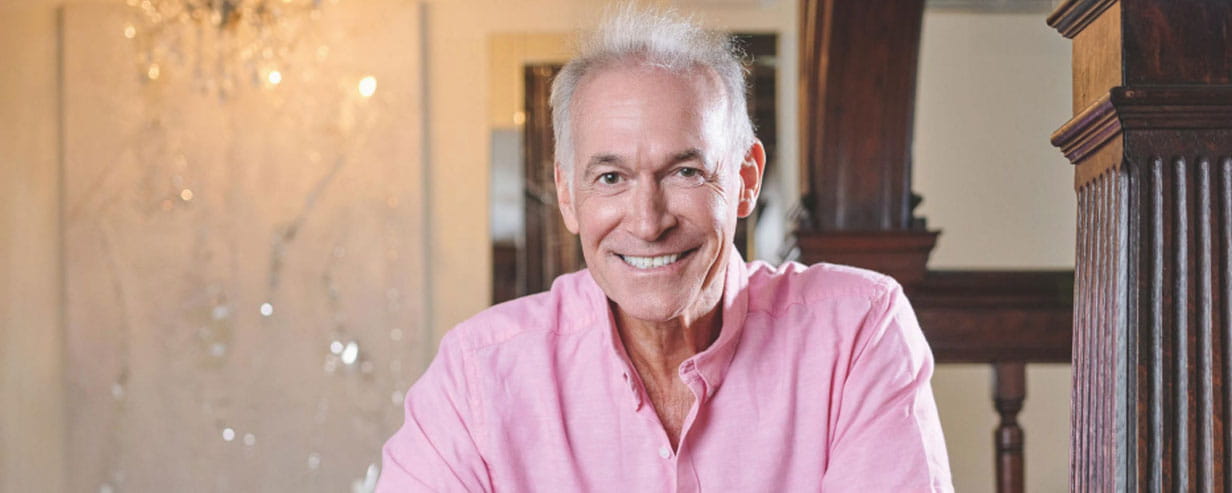

Dr Hilary Jones: “I wouldn’t want my children to be doctors now”

TV’s Dr Hilary Jones on why he wants sweeping reform to modern healthcare.

“What would David Attenborough do?” Gordon Buchanan on coming face to face with big cats

The wildlife filmmaker on his close call with a polar bear and why hanging out with lions is less scary than driving in the UK.

Adjoa Andoh on her Bridgerton future and being a famous grandma

The actress opens up to Jenni Murray on Saga's podcast Experience is Everything.

Prue Leith on Bake Off and learning to love being old

Dame Prue Leith talks about her secret to staying young and why she’s finally slowing down at 86.

David Olusoga on his extraordinary mum and The Celebrity Traitors

The TV historian on overcoming a difficult childhood and what it was like to appear on Celebrity Traitors.

Marian Keyes on staying sober and online scrolling

The Irish author, 62, on escaping the news through writing, staying sober and scrolling the internet for pretty things.

For a limited time, enjoy 3 issues of Saga Magazine for just £1. Receive the next 3 print editions delivered direct to your door, plus 3 months’ unlimited access to the Saga Magazine app—perfect for reading on the go.

Don’t miss your chance to experience award-winning content at an exceptional price.

Play our free daily puzzles

Beat the boredom and exercise your mind with our selection of free puzzles.