Gardens

Gardening and landscape design ideas to help you make the most of your outdoor living space.

Jobs to do in the garden in September

September is the perfect month to plan and plant for colour in the garden.

5 surprising items to help keep pests out of the garden, from the King's ex gardener

A former Highgrove gardener shares his advice. If they’re good enough for the royals, they’re good enough for us.

The best year-round fragrant plants, shrubs and aromatic herbs

How to pick the sweetest blackberries – and why they’re better for you than blueberries

Tips on foraging the sweetest, juiciest blackberries, how to grow your own and their surprising health benefits.

The best plants for winter containers

How to keep gardening no matter what your age or mobility

Jobs to do in the garden in September

September is the perfect month to plan and plant for colour in the garden.

Easy ways to save water in the garden and protect your plants

Jobs to do in the garden in April - 10 essential tasks to help you get ahead

5 surprising items to help keep pests out of the garden, from the King's ex gardener

A former Highgrove gardener shares his advice. If they’re good enough for the royals, they’re good enough for us.

Your free guide to autumn in your garden

7 beautiful places to see cherry blossom this spring

Perfect for browsing at home or on the go, the Saga Magazine app is packed with exclusive digital only content including interactive puzzles and games. You can even listen to some articles with our new audio feature.

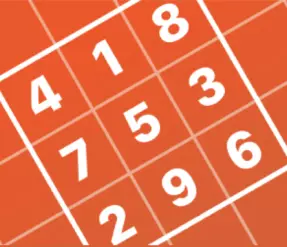

Play our free daily puzzles

Beat the boredom and exercise your mind with our selection of free puzzles.