From UK stays to global getaways

Get to know all about our insurance

A one-stop shop for existing customers

Extensive itineraries, expert guides, and hassle-free planning

Find your perfect hotel holiday with Saga

Booking, documentation & other queries

Access to a range of accounts to suit your savings needs.

Including will writing, probate and lasting power of attorney.

Provided by award-winning mortgage broker Tembo.

Tips, insight and guidance into helping your money work as hard – and stretch as far – as possible.

- Your guide to Inheritance Tax

- A guide to later-life mortgages and lending

- Gifting family inheritance

- Should you let your adult kids live at home?

- Getting a mortgage in retirement

- Maximising your property's selling appeal and value

- Lifetime mortgages vs Retirement Interest Only mortgages

- Second mortgages

The UK's bestselling subscription magazine

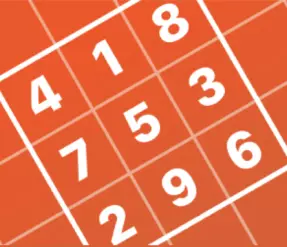

Discover our daily puzzles