Entertainment

Fun ways to pass the time, including TV reviews, ideas for days out, and interviews with top celebrities.

Hugh Bonneville on starting a new chapter

The actor bids farewell to Downton and looks forward to his starring role in a new West End show.

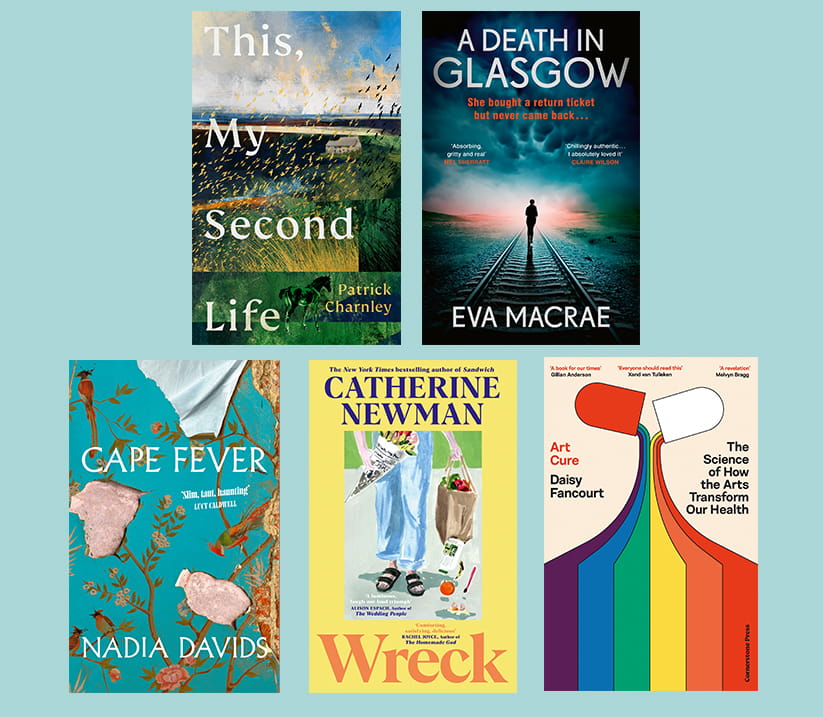

What to read in January 2026

The best new books to warm the soul, ignite the passions and set the pulse racing.

Sharron Davies on being cancelled and why she has no regrets

The former Olympic swimmer on the personal and financial toll of speaking out and her pride in becoming a Baroness.

Griff Rhys Jones on free speech and his alternative bucket list

The actor and comedian on his new comedy, rejecting a traditional bucket list and the secret to his 40-year marriage.

Curtain up! The best theatre to see in 2026

The must-see theatre and musical shows in the West End and on tour in the UK for the year ahead.

“There will never be another Paul O’Grady”

Nearly three years since the comedian's shock death, his best friend shares his memories of their time together.

Clodagh McKenna: “The right foods can lift your mood super-fast”

The TV chef talks happiness-boosting recipes and secrets for keeping the blues at bay.

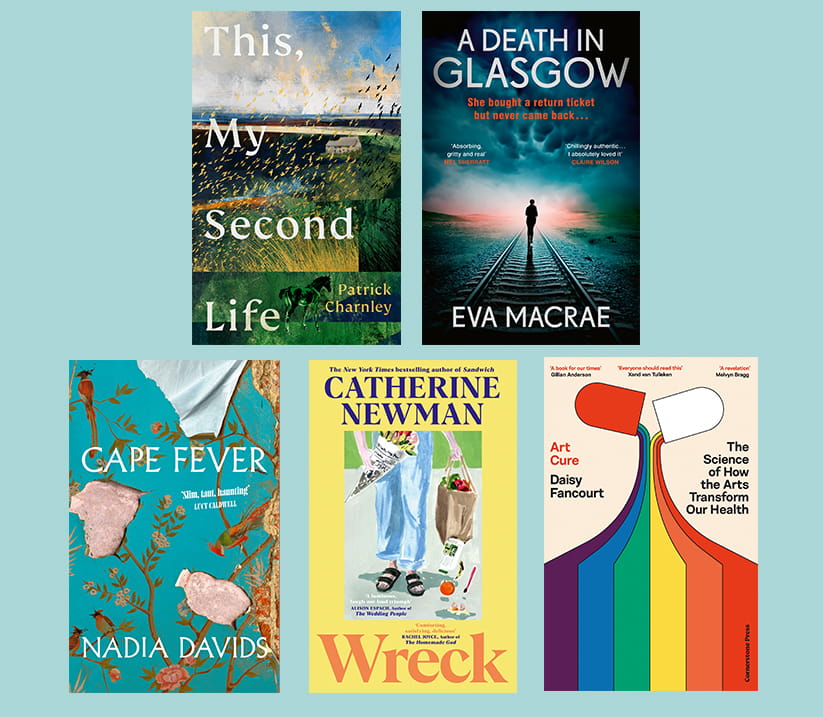

What to read in January 2026

The best new books to warm the soul, ignite the passions and set the pulse racing.

“There will never be another Paul O’Grady”

Nearly three years since the comedian's shock death, his best friend shares his memories of their time together.

9 fascinating facts about Guinness

Ahead of a new TV drama about the early years of Guinness, we've got some surprising facts about the world's favourite Irish beer.

Matthew Bourne’s The Midnight Bell – intoxicated tales from darkest Soho

Fern Britton talks This Morning, weight loss and a new unexpected joy

The TV presenter and novelist on how she’s open to love again and why she’s serving coffee in church.

Faulty Towers the Dining Experience review - "fun immersive theatre"

"A side-splitting night out" says our reviewer of Faulty Towers the Dining Experience - and it's touring the UK this summer.

Jo Whiley on why DJing is as good as a Jane Fonda workout

DJ and presenter Jo Whiley on how she's still getting home at 4am and why she thinks Monty Don is as cool as Mick Jagger.

For a limited time, enjoy 3 issues of Saga Magazine for just £1. Receive the next 3 print editions delivered direct to your door, plus 3 months’ unlimited access to the Saga Magazine app—perfect for reading on the go.

Don’t miss your chance to experience award-winning content at an exceptional price.

Play our free daily puzzles

Beat the boredom and exercise your mind with our selection of free puzzles.