Entertainment

Fun ways to pass the time, including TV reviews, ideas for days out, and interviews with top celebrities.

Tanni Grey-Thompson on prejudice and how competing left her broken

The 11-time Paralympian gold medallist opens up on Saga's new podcast Experience is Everything.

The Saga Magazine February pub quiz - From sweets, to fruit, to custard

Put your general knowledge to the test with our 20 brain-teasers.

Hugh Bonneville on starting a new chapter

The actor bids farewell to Downton and looks forward to his starring role in a new West End show.

What to read in February

Writing duos dominate this month’s novels, with fiendish plots and devilish humour.

“There will never be another Paul O’Grady”

Nearly three years since the comedian's shock death, his best friend shares his memories of their time together.

The best new TV dramas to start the year

Our pick of 6 top new dramas coming to our screens in January, plus earlier ones to catch up on that you might have missed.

Review: My Gardening Life by Mary Berry

The national treasure’s love of green spaces shines through in her new gardening book.

Tanni Grey-Thompson on prejudice and how competing left her broken

The 11-time Paralympian gold medallist opens up on Saga's new podcast Experience is Everything.

9 fascinating facts about Guinness

Ahead of a new TV drama about the early years of Guinness, we've got some surprising facts about the world's favourite Irish beer.

This year’s best cookbooks

Our choice of the 6 best cookbooks to buy for Christmas, filled with delicious inspiration.

Dame Zandra Rhodes: "A yoga class saved my life"

The iconic designer also reveals the secret detail in Princess Diana's dresses.

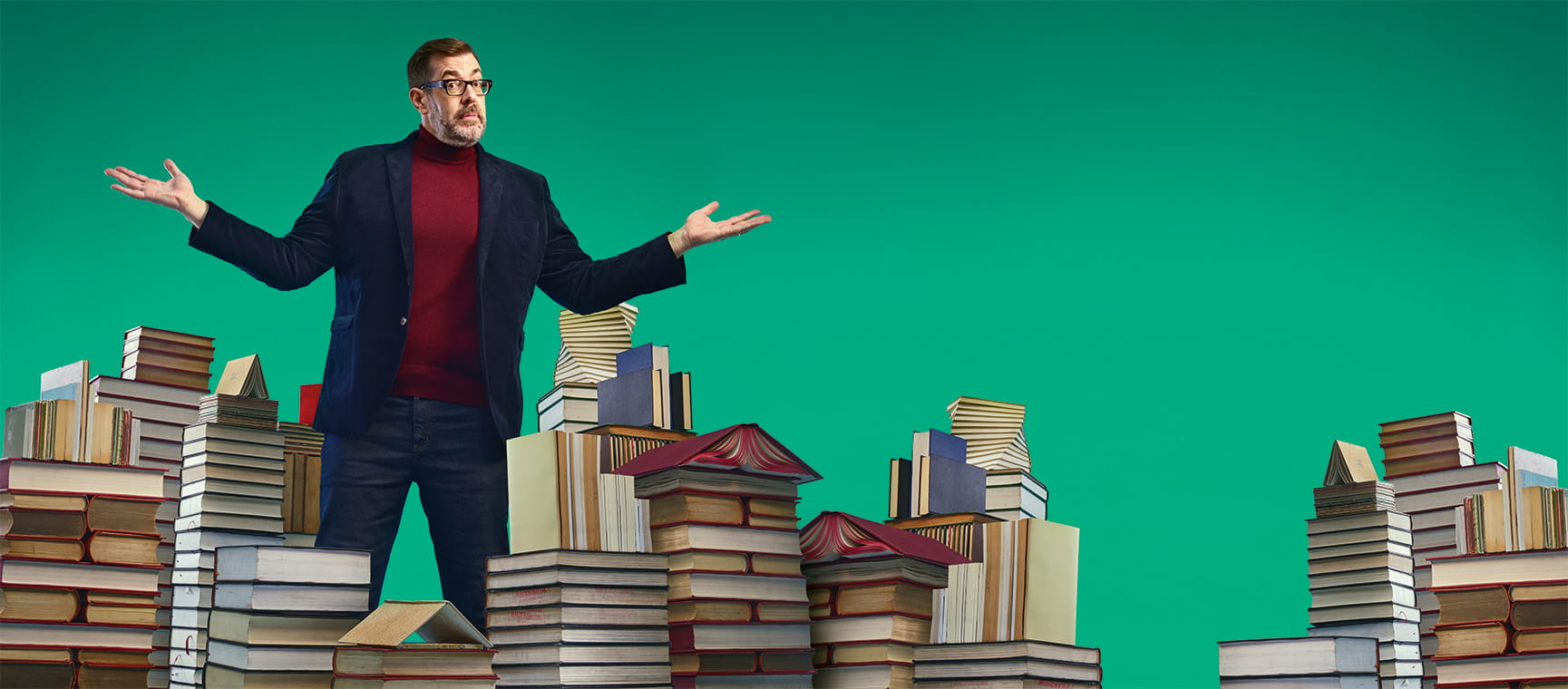

Richard Osman on his best-selling Thursday Murder Club series

Women’s Euro 2025: everything you need to know

As England and Wales gear up to take on Europe's elite, here's our guide to football's big summer showcase.

Royal tips for the perfect dinner party – and what you’re doing wrong

King Charles’ former butler Grant Harrold shares his 5 secrets for dinner party success.

For a limited time, enjoy 3 issues of Saga Magazine for just £1. Receive the next 3 print editions delivered direct to your door, plus 3 months’ unlimited access to the Saga Magazine app—perfect for reading on the go.

Don’t miss your chance to experience award-winning content at an exceptional price.

Play our free daily puzzles

Beat the boredom and exercise your mind with our selection of free puzzles.